skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I think, of all the stories I've addressed so far, Ender's Game, by Orson Scott Card, is more science fiction than any other. This applies from a classical-definition-of-science-fiction standpoint (it's a book about alien invasions in the future with spaceships and stuff), and from the standpoint of my own definition of science fiction, for reasons that I'll talk about in a paragraph or two. What makes Ender's Game most notable, however, is how elegantly it's able to represent the way in which science fiction's proclivity for the former enables it to clearly convey the latter.

In my opinion, Ender's Game represents one of the most comprehensive studies of morality (in particular, the moral laws that govern the use/abuse of power by authority figures) that has ever been written into fiction. However, the plot that sustains this fascinating philosophical exercise is, on its surface, utterly sophomoric. Ender Wiggin, a child of six, is inducted by the military into "Battle School," a place for children like him to be trained into the generals that will fight off a potential invasion by the "Buggers," a race of violent, insect-like aliens. As Gerald Jonas wrote in his (very positive) review of the book for the New York Times, it "sounds like the synopsis of a grade Z, made-for-television, science-fiction-rip-off movie."

Alternate history is one of those subgenres that's typically associated with science fiction, but there's nothing inherently "science fiction-y" about it. Certainly, you can't claim that it's a part of "normal" non-speculative fiction since its version of history is alternate. In addition, many of its most famous examples, including such classics as Harry Turtledove's The Guns of the South, use science fiction-y elements like time travel to create the alternate realities in which they occur. On the other hand, there are plenty of examples of works in which the only speculative device the author uses is the alternate history itself; one of the most notable of these is the work that I'll be focusing on today: Philip K. Dick's Hugo-winning novel The Man in the High Castle.

Recently, I've been on a Cowboy Bebop kick, so I figured I'd address it in this week's blog post. For the uninitiated, Cowboy Bebop is an anime series revolving around the exploits of a team of bounty hunters in a spaceship called the "Bebop." It's set in 2071, when Earth has been decimated by a terrible accident, leading its inhabitants to terraform and colonize the solar system's other planets. In addition, it has one of the most fantastic soundtracks of any TV series, ever. Is it awesome? Absolutely. But is it science fiction? Unfortunately, no.

So why isn't it science fiction?

A middle-of-the-week tangent:

Philip K. Dick is the writer that I admire most in the world. He's best known as the author of the stories that formed the inspiration behind Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report; over his (far too short) life, he wrote 44 novels and over a hundred short stories, which collectively represent one of the richest and most significant bodies of work in the history of science fiction. But more important to me than all his fiction combined is a little-known and little-read essay entitled "How to Build a Universe that Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later."

Philip K. Dick is the writer that I admire most in the world. He's best known as the author of the stories that formed the inspiration behind Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report; over his (far too short) life, he wrote 44 novels and over a hundred short stories, which collectively represent one of the richest and most significant bodies of work in the history of science fiction. But more important to me than all his fiction combined is a little-known and little-read essay entitled "How to Build a Universe that Doesn't Fall Apart Two Days Later."

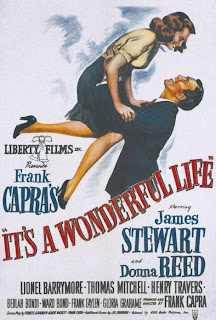

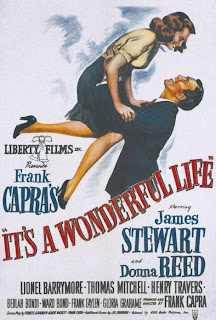

"What?" you think. "It's a Wonderful Life is definitely NOT science fiction. Why are you even bothering to ask?" Well, I do think it's science fiction, and here's why:

It honestly doesn't take much to begin to imagine It's a Wonderful Life in science fiction terms. The angels, for example, taken out of their spiritual context, become an advanced extraterrestrial race. In fact, even within their spiritual context, they are still a race of enormously powerful beings from outside the Earth—literally, an advanced extraterrestrial race. They use their powers to take human form and to transport George Bailey to an alternate universe in which he had never been born; both of these plot devices are firmly established within the science fiction realm. With these things in mind, why ISN'T It's a Wonderful Life science fiction?

As much as it pains me to say it, Avatar is indeed science fiction.

It was trying pretty hard not to be science fiction, though. Its characters, you may have noticed, were pretty weak. And its plot definitely didn't need to be science fiction to get its message across; numerous people have noted that the plots of Avatar, Dances with Wolves, and Disney's Pocahontas seem to have been created by filling in the same Mad Libs sheet.

So what is it that makes Avatar science fiction? In short, the "avatar" concept. By including this concept in the film, James Cameron created a reality that asks the question "What makes us human?" And it asks the question really, really well.

No. In my opinion, Superman isn't science fiction.

"Why not?" you may ask. "Superman's an alien being! He's from another planet! He visits an Earth that is clearly analogous to our own!" Yes, all valid points. But none of these things make the film true science fiction.

First, examine the setting in which Superman takes place. It is indeed an Earth very much like our own; it's got a Grand Canyon and a San Andreas Fault and a United States and all sorts of other Earth-y things. But it's also got a Metropolis. Not only is "Metropolis" not an actual city, but it's a city that was designed specifically to be an allegory for every major... metropolis in the United States (hence the name; they may as well have called it "Big City"). Furthermore, while Metropolis is located somewhere in the US, it isn't explicitly or implicitly located in any particular state. Metropolis is not an alternate reality, rather it's a mere metaphor for reality, lacking the depth and specificity of a fully fleshed-out world. The characters follow this same pattern: Lex Luthor is a villain, Superman is a hero, Lois Lane is a love interest. These are not actual people populating an actual reality; these are symbols of good and evil populating a fable.

Science fiction is a topic about which I am very, very passionate. I will, if you allow me, talk for hours and hours about science fiction. I'll expound on dystopia and wax lyrical on post-apocalypse. And I'll do all this for a genre that, really, lacks definition.

I'm sure that you have some idea of what science fiction is--or, at least, what the phrase means to you. But bookstores and genre literary magazines (not to mention the ridiculous SyFy cable channel) tend to lump science fiction and fantasy together in a larger "speculative fiction" category. I find this abhorrent. To me, science fiction and fantasy represent completely different concepts. On opposite ends of the spectrum. Diametrically opposed. And for whatever reason, I can't find anyone else who gets this worked up about it.

So I've started this blog. Every week, I'm planning on coming back and addressing a work of TV, film, or literature, then explaining why it deserves or does not deserve to be called science fiction. Hopefully, someone out there in the vast internet collective will be as passionate about this topic as I am.